The National Referral Mechanism system is changing. Established in 2009, the NRM is a framework for identifying potential victims of human trafficking and modern slavery, ensuring that they receive appropriate multi-agency support. It also informs the national intelligence picture around modern slavery e.g. identifying particular vulnerable groups and countries where people have been trafficked to and from.

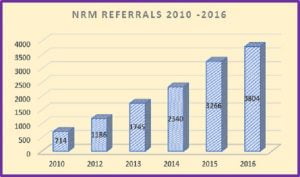

In the eight years that it has been in existence, has it been successful? I believe it has, but like many new pieces of legislation or statutory guidance, they are often slow burners at the start, taking some time to bed into those organisations who the legislation affects. Many acts need tweaking and improving on. If the NRM was purely judged on numbers, then it can be adjudged to have been a success. Between 2010 and 2016, year on year referrals have risen consistently at an average 40% each year. From 714 referrals in the first full year, that figure has risen steadily to 3,804 in 2016. This is of course not reflective of the true number of modern slavery cases in the UK, in fact it is just the tip of the iceberg, for the real challenge is identifying those people that are affected by modern slavery.

Table: Yearly number of NRM referrals (exclusive of 2011).

Strangely, the average rise didn’t materialise last year, with referrals up by only 538 (16%) on the previous year. This is odd given that this was the first full year since the introduction of the Modern Slavery Act 2015, when the fight against modern slavery and human trafficking was at the forefront of the safeguarding spotlight. Whilst there were still 3,804 referrals , I would have expected to have seen an increase, rather than a drop in what had been a fairly healthy year on year increase. This may be something to do with the ‘duty to notify’ introduced by the 2015 act. This then new provision, made it a requirement for certain agencies to notify the government of all potential adult modern slavery and human trafficking victims, regardless of whether they consent to the NRM process or not. Last year the duty to notify identified a further 782 potential adult victims in addition to those referred through the NRM process, bringing the total to 4,586 which brings the increase to 35%, more in keeping with the average.

Whilst the increase in referrals has been consistent and steady, there have been question marks over whether the system itself was efficient and providing enough effective support to those that are referred into the process. The need to change was recognised sometime again and changes have already been made . For example when the NRM was initially established, it dealt solely with victims of human trafficking and in 2015 it was extended to cover victims of all forms of modern slavery. This timeline of change began in April 2014 when Theresa May, the then Home Secretary, commissioned a review of the NRM system to “establish whether it provided an effective and efficient means of supporting and identifying potential victims of human trafficking”. It also looked at whether the scheme should be extended to cover modern slavery. In November 2014 the review reported back and made the following main recommendations:

- extend the NRM to cover all adult victims of modern slavery

- strengthen the first responder role – the point when potential victims are first identified and referred – by creating new Anti-Slavery Safeguarding Leads, allowing direct referral to specialist support

- establish new multi-disciplinary panels, headed by independent chairs, to ensure that decision-making on cases was extended beyond UK Visas and Immigration and the UK Human Trafficking Centre in the National Crime Agency

- create a particular case working unit within the Home Office to replace the current units in UK Visas and Immigration and the National Crime Agency

Theresa May responded to the report and set out the governments modern slavery strategy in the same month, stating that the government was committed to “extending the support offered through the NRM, including accommodation and subsistence, to potential victims of all forms of modern slavery in England and Wales”. She announced that the Home Office would be working with interested partners to pilot changes recommended in the NRM review. These 1-year pilots began in August 2015 in two police areas, one in the north of England, the other in the south west. After the pilot scheme ended, the evaluation process began. The wheels of government turn slowly, and we have had an election in the interim, where the majority of ministerial business ceases for a significant period. Therefore, it wasn’t until October 2017 that the fresh changes to the NRM process were announced by the Minister for Crime, Safeguarding and Vulnerability, Sarah Newton.

What are the changes?

The proposed changes are:

- minimum standards of care introduced during the reflection and recovery support period.

- the establishment of ‘places of safety’ for potential victims, providing immediate support for up to 3 days, giving them time to decide whether to enter the NRM. This is particularly useful for those victims that are rescued by immigration or law enforcement agencies.

- a significant increase in the minimum period of ‘move-on’ support for victims, such as ongoing accommodation, counselling, expert advice and advocacy. This will be extended from 14 days to 45 days (in addition to the 45 days following a reasonable grounds decision).

- up to 6 months of ‘drop-in’ services, developed in partnership with The Salvation Army, for those transitioning out of the NRM.

- the national roll out of Independent Child Trafficking Advocates, to provide specialist support for trafficked children.

- working with local authorities to identify best practice for victims to make the transition into a community and access local services.

- aligning subsistence rates provided to victims of modern slavery to those received by asylum seekers.

- the creation of a single, expert unit in the Home Office to handle all NRM cases and deal with both the reasonable and conclusive grounds decisions. This replaces the current system of two different organisations – the National Crime Agency and UK Visas and Immigration. This is aimed at achieving quicker conclusive ground decisions.

- an independent panel of experts to review all negative decisions.

- the rollout of a new digital system to support the NRM process, making frontline referrals easier and enhancing data capture and analysis.

On the face of it, these changes look decent, but have they gone far enough? The UK’s Anti-Slavery Commissioner, Kevin Hyland commenting on the reforms said “I am extremely pleased that we have been able to rectify shortcomings, develop solutions and commit to improve the lives of those who have suffered. This is a significant step forward in the fight against modern slavery.”

There was however, a more cautious approach from the leading children’s rights organisation ECPAT UK, who work tirelessly to protect children from child trafficking and exploitation. ECPAT welcomed the reforms as a step in the right direction but stated that the proposals “do not go far enough to protect child victims of trafficking and provide them with the specialist care they need”. ECPAT called on the government to do more to ensure that child victims of trafficking are properly identified. They took issue with the fact that civil servants within the Home Office would now be responsible for making reasonable and conclusive grounds decisions for children, rather than a best practice multi-agency approach. Furthermore, they argued that “child victims of trafficking should be embedded within existing child protection systems, based at a local level with trained multi-agency child protection actors”. They argued that the “reforms do not address the fact that local authorities need more resources to provide this level of support”.

As a person involved in safeguarding, I agree wholeheartedly with their comments. There needs to be a joined up multi-agency response to trafficking in every local authority, and a commitment from central Government to invest funds and resources. After all, it was the current Prime Minister who in 2015 called Modern Slavery “the great human rights issue of our time” and vowed to make it her mission to “help rid the world of this barbaric evil”. Under her government there has undoubtedly been progress. However, historically many safeguarding professionals wrongly associated the NRM with people who have only been trafficked into the UK, overlooking the issue of children being trafficked around the UK for sexual and criminal exploitation. That view needs to change.

For the last several years we have seen the phenomenal rise of County Lines organised drug networks. The number of UK children that are being trafficked around the UK by these networks is staggering. It is already out of control and increasing. Safeguarding agencies are playing catch up and although slow to react, safeguarding professionals are beginning to realise that the NRM might be appropriate in county lines cases. This means many more UK young people will potentially be referred into the process. What concerns me is that the NRM system hasn’t caught up to the prospect of trafficked children through county lines. I am not convinced that the ‘recovery and reflection’ period they would be entitled to would actually work, and that specifically children already in care will not benefit at all.

The NRM is a separate process to normal safeguarding procedures, complimenting but not replacing the requirement for the responsible authority to instigate or continue with child safeguarding measures. I see a danger here for young people, in that they may get caught in ‘no man’s land’, where we think that referring them into the NRM is the answer because we run out of ideas for other interventions. Meanwhile, the ability of the NRM process to provide them with the independent emotional and practical help they need will be poor and inconsistent, because across large parts of the UK there is a lack of voluntary agencies that specialise in diverting young people away from county lines or gangs. The Salvation Army’s have the contract to provide NRM support and whilst their subcontractors bring a wealth of excellent experience and support to the table, I am not convinced that they can offer the specialist support required for what may be a substantial increase in referrals for criminally and sexually exploited UK born children. I was recently at a brilliant ‘Safeguarding Migrant Children’ conference, hosted by colleagues in Hertfordshire and shared a table with two people that work in 2 of the 3 areas that already have Independent Child Trafficking Advocates in place. The feedback on the work of these ICTA’s was positive, and they appear to have had a significant impact and role to play in these two areas. However, it appears that the national rollout of ICTA’s might not happen until 2019 and I question whether there will be enough of them to cope with demand in certain parts of the UK. So, whilst the amendments to the NRM are positive, I will nail my colours to ECPAT’s mast and say that much more needs to be done to protect child victims of trafficking.

Our useful factsheet for the current NRM provisions is available here: NRM Factsheet

We will of course update it when we get a clearer picture of how the changes will work.

You can access ECPAT UK’s campaign through their website : ECPAT UK

In relation to your article regarding the NRM. I agree. Working in law enforcement and as a child vulnerability and CSE officer I battle daily with colleagues who see the process as one that juveniles can use to get out of prosecution. There is a long way to go before everyone “gets it” a child is exploited and not necessarily a criminal. Good article.

In relation to your article regarding the NRM. I agree. Working in law enforcement and as a child vulnerability and CSE officer I battle daily with colleagues who see the process as one that juveniles can use to get out of prosecution. There is a long way to go before everyone “gets it” a child is exploited and not necessarily a criminal. Good article.

Thanks Julie. Really appreciate the positive comments and thanks for reading the article. Completely agree. Changing the culture among colleagues is one if the biggest challenges we face.

Thanks Julie. Really appreciate the positive comments and thanks for reading the article. Completely agree. Changing the culture among colleagues is one if the biggest challenges we face.